Acknowledgements

The following text is a translation of pages 11-39 of "Aesóp gConamara" edited by Professor Nollaig Mac Congáil (published by Arlen House, 2009, ISBN978-0905223-67-4).

We wish to express our heartfelt gratitude to the family of Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill, namely Cian, Diarmuid and Nuala for their help when we were establishing the facts relating to Domhnall's biography. Diarmuid has earned special thanks for alerting us initially to the important role his father played in the life and study of the Irish language over many years, which was an 'eye-opener' for us and for providing manuscripts, newspaper cuttings, photographs etc. Their courtesy and generosity were akin to their father's.

Thanks are due to Máire Uí Chuinneáin for her contribution. Proper research cannot be conducted without resorting to a library and we are obliged to the staff of the following libraries: James Hardiman Library, NUI Galway, the National Library and Pearse Street Library, Dublin. We are also grateful to the staff of the Department of Folklore, UCD for their assistance.

Above everyone else, we are greatly obliged to Pádraic Mac Con Iomaire and Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill, both of whom understood the importance of the heritage that they had inherited and left as a legacy to us.

Introduction

In recent times, few columns in Irish are to be seen in the English language newspapers of Ireland, be they national or local, evening or Sunday papers, apart from the occasional one here or there. The print media have entirely marginalised and almost completely forgotten the Irish language for many years. That was not the case during the last century, particularly after the establishment of the Irish Free State. The English language newspapers, albeit on a small scale, used to cultivate Irish, as they felt that the Irish public were interested in that commodity, and according to their own ideology. Undoubtedly, the public's interest was neither lasting nor constant in regard to Irish and as a consequence, the cultivation of that language in the English language newspapers suffered. In truth, print media in Irish, even when at its best, belonged only to a tiny number of readers throughout the country in the last analysis. As against that, the English language print media related to the general public of Ireland and that was the case for a long time. One should, therefore, remember the importance of the English language media in advancing Irish in so many ways and the enormous extent to which the Irish language's cause was advanced by them by every means for so many years during the twentieth century.

We shall recount in the following pages the achievement of one such English language newspaper in the early 1940s, namely, the Evening Herald. It is true that Irish was also being cultivated in the Evening Herald long before then and also in the Irish Independent and Irish Weekly Independent, both papers belonging to the same company. Thus, a new series in Irish was presented to the public towards the end of November 1941:

Some time ago, we published a series of 'Bird and Beast' studies by Pádhraic Mac Con Iomaire, the well-known seanchaidhe from Carna, Co Galway. These short articles were evidence of keen observation, coupled with a remarkable gift of easy expression. Pádhraic has since carried off first prize for story-telling at Oireachtas na Gaedhilge. A special correspondent of the Evening Herald has written down from his dictation a large number of Aesop's Fables told in his own imitable way. The first instalment in this new series will appear on Monday.

Native Irish versions of Aesop's Fables were written down by Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill, a great exponent of Irish and folklore from the oral narrative of Pádraic Mac Con Iomaire, from Carna, one of the most famous seanchaís ever. Domhnall had for long been visiting Pádraic and Carna, seeking that folklore which so much interested him. As will be seen from the following account of his life, Domhnall was a great 'Gaeilgeoir' and folklorist and he sought to serve two ends in this series. He wished to add to the corpus of Irish reading and literature in Irish through supplying native Irish readings of Aesop's renowned fables. Here is how Domhnall described the history and modus operandi of this initiative:

I gave an English version of Aesop's Fables to Pádraic Mac Con Iomaire, the notable seanchaí in Carna, and asked him to give his own version in Irish of these small stories. He did not want any translation of the sayings to be made, but provided a natural Irish version of them. He narrated them just as he would narrate any of the hundreds of stories contained in his own seanchas. Here readers, are some samples of Pádraic's attempts to put a true Irish gloss in Aesop.

Over one hundred pieces were printed between November 1941 to the end of 1942, a few per week. No translation accompanied them.

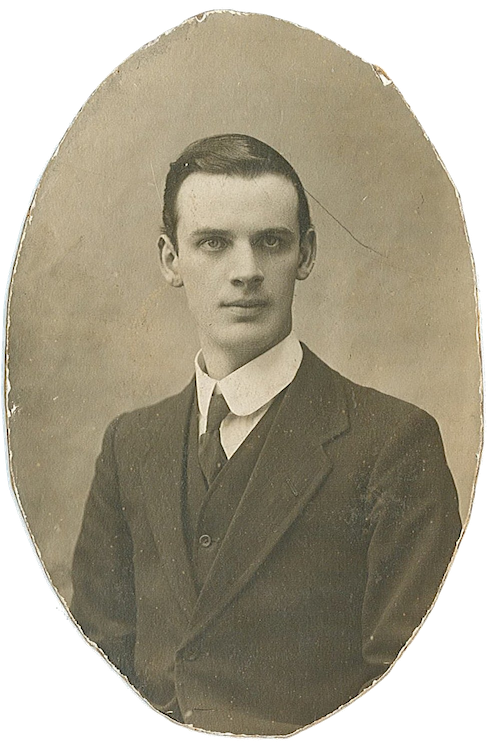

Biography of Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill 1891-1963

Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill was born on 7 January 1891 in the townland of Cloneganna, which is located about one mile from the village of Dunkerrin, Co Offaly and approximately seven miles south west of Roscrea. He was the son of Daniel Carroll and Sarah Bergin. Daniel was a twin brother of Michael. They were born on 2 February 1843, two years before the Great Famine. There were also three sisters in the family. The Carroll family had a small holding of 36 acres on the north side of the lower Cloneganna Road. They were known as the Carrolls (Dan). Another family lived north of the same road who were also called the Carrolls (Bill), because William Carroll was the head of that household.

Daniel grew up on the farm. It seems that he was educated in Cloneganna National School. He qualified as a primary school teacher but it is not known for certain how this occurred. It is possible that he won one of the King's Scholarships, which would have enabled him to gain higher education at the Model School in Dublin. In the absence of any definite information to that effect, the second opinion exists regarding how Daniel was trained to become a national teacher, that is, that he spent some years as a monitor until he was appointed as a teacher at the age of twenty. He served as principal of Cloneganna National School from 1863 until 1908. He educated his pupils well and many pursued good professions over the years in public service and in the life of the Church. He was also well known as a land surveyor and it is said he walked all the way to Dublin and back to collect a circumferentor, an instrument frequently used by him while surveying. Daniel undertook the survey of the land on which the Cistercian monastery of Roscrea now stands. Many a mile he walked while doing this work.

Daniel was also a fine musician, a famous flautist who played a very special version of the Fairy Reel, that he had heard in the fort (dún) at the back of his residence, the Stump House. This house was bought from the Scanlon family who emigrated to America in 1900. It is believed that Domhnall helped generously with the purchase of this house and land for his parents in the 1920s. There were 80 acres on this farm. The house originally belonged to an Egan family and it was in that house that Bishop Egan who became Bishop of Waterford and Lismore was born. Indicative of the good example and guidance given by Daniel and Sarah to their growing family was that three of their daughters joined religious orders. Daniel's grandson, the late Monsignor Donal O'Carroll, compared him to the Village Schoolmaster in Goldsmith's poem 'The Deserted Village': 'it was certain that he could gauge and cipher too.' The Monsignor died in Spring 2005.

Daniel and Sarah had nine children, namely Mary, Michael, Anne, Margaret, Bridget, Catherine, Daniel (Domhnall), William and Patrick (it could well be that his name was Patrick Joseph initially, given that his family called him Joseph). William, a schoolteacher, was involved in the Fight for Freedom. Patrick, the youngest son was a farmer and mechanic and fought with the Old IRA. Mary, Anne and Bridget went away to become nuns. Mary (Sr Margaret) went away to Indiana and Bridget (Sr Teresa Joseph) to the Convent of Mercy at Pope's Villa in Twickenham, England, where she taught. Anne (Sr Prospera) stayed at the Convent of the Good Shepherd in Limerick. Mary never saw her brother Domhnall as she went away to join the nuns before he was born. Of the nine siblings, five were associated with teaching. Catherine (Harton) was a national teacher and both she and Margaret (McCormack) married two Cavan men who had come to live in the neighbourhood. Domhnall was the third youngest son.

Following his primary education in Cloneganna, Domhnall went to the Cistercian secondary school at Mount St Joseph's, Roscrea in 1906, where he was one of the very first day pupils. The teacher used to call him the 'Cloneganna Express' as he welcomed him each morning after his three-mile walk to school from his home in Cloneganna. Among the subjects he learned were English, Irish, Mathematics, French and Experimental Physics. Subsequently, he attended the De La Salle Training College in Waterford where he was awarded a first class Diploma of Teacher as a Christian Educator in 1913. He commenced his teaching profession from 1914 onwards at Denmark Street, Dublin. He graduated with a Diploma in Education at UCD in 1926; this was a two-year course. In 1928, he was awarded the BA degree at UCD. He took the Higher Diploma in Education in 1929. He spent a spell teaching at Coláiste Laighean in Dublin. He began teaching at the Sacred Heart School, Glasnevin in the late 1920s and became principal there subsequently. This school stood at Church Avenue, near the bottom of Ballymun Road, where the Glasnevin Educate Together school now is - close to Met Éireann and the Holy Faith Convent.

2 Cremore Park

He married Teresa Ford from Gurteen in east County Galway in the Church of Saint Columba on Iona Road, Glasnevin on 24 July 1928. They lived at 2 Cremore Park, Glasnevin after they married close to the school where Domhnall spent the remainder of his teaching career. Teresa (Tessie) was a sister of Seán Mac Giollarnáth. Seán was well known in Connemara during these years as a District Justice and as a collector of folklore.

Domhnall & Teresa

Domhnall and Teresa had three children, namely Diarmuid, Cian and Nuala. Diarmuid was a lecturer in the Department of Economics and Dean of the Faculty of Commerce, at University College Galway between 1967 and 1995. Previously he had worked at the Department of Finance in Dublin. He is married and now lives in Galway. Cian started as an auctioneer in Dublin. He is married and resides in Limerick. He was Estates Manager of Shannon Free Airport Development Company (SFADCO) and subsequently Manager of Shannon Heritage. Nuala is the youngest of the family and worked as an executive of SFADCO, dealing with European affairs in Limerick.

Domhnall was a man endowed with many skills. It is clear from his extensive works that he had an interest in the Irish language, craftsmanship, nature and the world surrounding him. Just like his father before him, there was little that did not bear the impact of his handiwork. He was also a superb collector of folklore. He was appointed to the Committee of an Cumann le Béaloideas in January 1936, of which he remained as a committee member until 1961.

He, Teresa and their family spent holidays in Carna in the 1930s where they rented a cottage in Moyrus. One day when walking along the road in Carna during one of those holidays, he noticed a particular garden where carrots were growing. The man who owned the garden noticed him also and saluted him, inviting him into his house. That man was Pádraic Mac Con Iomaire from Coillín in Carna. Pádraic was a famous seanchaí from whom Domhnall collected many stories and much folklore. Domhnall used an ediphone to record the stories and subsequently wrote them into copybooks. Pádraic provided him with much information about the district and what life was like in that part of the country as he grew up. This information and the stories collected by Domhnall from Pádraic were published in the Irish Weekly Independent and Evening Herald between 1934 and 1942. A great friendship developed between Pádraic and Domhnall who presented a handloom made by himself to Pádraic's family. This friendship has persisted ever since as Domhnall's son Diarmuid visited Áine (RIP) and Cáit in Boston, USA.

Another notable seanchaí met up with Domhnall while he was staying in Carna; he was Pádraic Mac Dhonnchadha (Pat Bhilly), also from Coillín. He too gave Domhnall some stories and folklore concerning the district, which were also published in the Irish Weekly Independent between 1934 and 1939. Domhnall also met local craftsmen. The Caseys of Maoinis were, of course, very famous boat builders and a piece written by Domhnall 'Notes on a Connemara Currach', is to be found in Béaloideas 1939-1940. One of the Maoinis people (Jennings?) presented Domhnall with a model of a sailing boat. Domhnall had a great interest in carpentry and he collected a lot of information from Pádraic Ó hUaithnín of Dubh Ithir, Carna; he was a first class carpenter. This information that he gave to Domhnall – ‘Seanchas na gCeard’ – appeared in the Irish Weekly Independent, in June 1935. Domhnall himself was a superb carpenter and articles entitled ‘Seanchas Siúinéireachta’, were published in the Irish Weekly Independent from 6 July 1935 to 7 September 1935.

Domhnall spent some time in Aran in 1942 and collected a story in Inis Meáin: ‘Curadh Glas an Eolais’ from Ruaidhrí Ó Tuathaláin. In Domhnall’s opinion, Ruaidhrí had taken this story from a book. Domhnall photographed about 150 pictures of material folk culture of Aran. It may well be that Domhnall presented these photographs to the National Museum along with others that he took while researching folk life and culture in Sweden in 1936. He met an old man, Seán Ó Conghaile (Tomás?) in Inis Oírr who built currachs and showed him how to make an anchor, a keeler and a currach. Domhnall took many pictures of this work. This man was able to construct spinning wheels and had orders for five or six of them. He had to buy the materials for them in Galway. Domhnall pitied him because of the high cost associated with this craft and recommended that someone should go around to assist craftsmen like Seán Ó Conghaile. Domhnall made six stocks (centres) of wheels (imleacáin) for him and Seán recompensed him for this work by sending him panniers and baskets. Domhnall also collected folklore stories from Seán Ó Coileáin, the notable seanchaí from Cor an Dola.

Domhnall’s high reputation among the famous folklore scholars was mentioned by Gearóid Mac Eoin when welcoming Éire, a new annual in Irish. His name was also among the eminent scholars who were about to provide folklore stories in a new column in the Irish Independent for Saint Patrick’s Day in 1940. He was gifted as a writer and as is evident from the bibliography of his writings, he took full advantage of that talent. He had various types of articles printed in the Sunday Independent between 1922 and 1925.

In April 1922, the Sunday Independent started a column for learners of Irish. Domhnall played his part in providing Irish material, stories and translations to that paper. The same applied to the Irish Independent, the Irish Weekly Independent and the Evening Herald. He also had some essays printed in the Irish Press. One could say that he was a buttress of the English language newspapers from an Irish language perspective from the early 1920s to the 1940s. He also translated a few books. One was published as a book, namely Robin Huid, but none of the other translations were ever published in book form. He provided a great variety of topics and never duplicated any of the topics in any of the newspapers.

Domhnall had a specific interest in domestic industries. He spoke about those industries at the annual meeting of the National Agricultural and Industrial Development Association (NAIDA) in St Stephen’s Green, Dublin in 1939. Certain matters exercised him in this regard. He perceived the many changes that ensued for people’s lives from the Industrial Revolution. The ‘old life’ was coming to an end, as were the people’s work and culture. He firmly believed that the remnants of the old life should be collected, preserved and displayed in the National Museum.

Early in June 1936, he went to Copenhagen to study the Cultural Museum that was there. A diary which he kept describes how a man named Mr Smith brought him sight-seeing through the city. He brought him to a museum in Lyngby where he viewed old houses and windmills. Each house, including its furniture and walls, was transferred exactly as it had stood in the countryside. This was easily managed as the walls were made of timber posts with clay or mud between them. The date was written above every lintel and on each box; this was a national custom, which greatly facilitated folklorists. Rooms from the houses of the gentry were also on display. He went to Glypoteck Museum, where exhibits relating to the Bronze Age were magnificently arranged. He met with Dr Orlick who brought him into a part of the museum that was not yet open and not ready for opening for another two years. Rooms from houses were being erected by carpenters there and dated just as was the case in Lyngby. He moved from there to Det Danske and the Kurtindustrimuseum. Superb handicrafts of many kinds were on display there and chronologically arranged, according to the time they were made. According to Domhnall, a brewer had donated the money required to establish this museum. He was told that one man had donated a million kroner in order to develop the Folkemuseet. Domhnall reported that Mr Smith told him that it was a shame that the Claddagh in Galway was being demolished without any samples of it remaining.

Domhnall then boarded ship for Malmo, where he met A. Nillson, who secured lodgings for him with the director of the Museum. He and Mr Nillson visited the Museum where some implements were on display. He explained what use was made of them while Domhnall noted down all that he had observed. Nillson explained to him a new scheme to register items that could be adapted for use in Ireland. Domhnall regretted that he himself knew little or nothing about spinning matters, as the machines were so simple. Every item in the Museum was set out so as to show how the people lived. This was the kind of museum needed for this country, in his opinion. He made notes of all he saw during his visit, often drawing these objects. On his return, in the course of a lecture at Wynn’s Hotel in Dublin, he explained how folklore was being collected in Sweden. He used lantern slides produced by himself from all sorts of things to explain the story he was telling. He stated that no seanchaí or folklore stories were to be found in Sweden, unlike Ireland. Students in that country study work methods, old trades and craftsmanship. University students are sent out to various parts throughout the country, taking notes on work methods and tools being used by the people. The students furnish this information to the Museum and if they discover any particular items of interest, qualified persons are sent out to examine them. According to Domhnall, the Swedish collectors had no interest in archaeology but directed their attention to the people’s culture. They studied place-names and various dialects. He spoke also of the time he spent in Connemara within the context of his Swedish experience and explained the study he had made of work methods and crafts in Ireland. He stated that the old crafts had been passed from generation to generation throughout Europe and were being studied by students.

Professor Patricia Lysaght has given an account of Domhnall’s visit to Sweden and of the official justification for it:

Among the people – apart from Seán Ó Súilleabháin who received training in Swedish archival and field methods, was Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill, a National School teacher with a keen interest in material culture. In the early 1930s he was being groomed by Séamus Ó Duilearga in anticipation of the setting up of a folk museum based on the Skansen model in Stockholm, which was being enthusiastically mooted at the time. He spent two months in Sweden (June-July 1936) with Dr. Albert Nilsson (later Eskerod) in Lund, and Dr. Ake Campbell in Uppsala, at the Commission’s expense, being trained as a material culture specialist. He was never employed in that capacity, however, as the folk museum project faltered and eventually just faded away.

Domhnall was due to be appointed in 1939 as director of the National Folk Museum under the auspices of the National Museum in Phoenix Park but this project had to be cancelled on the outbreak of war.

Domhnall was also a radio broadcaster. He had a regular radio programme on air every Saturday night from 1940 to the mid 1950s. Making and Mending was the main title of this programme and he used the pen-name Peadar O’Connor. The following extract describes the programme and the gifts of the person in charge of it:

ADVICE FOR THE ‘HANDY’ MAN

Listeners may like to be reminded that Saturday evening next, 20th, Peadar O’Connor returns to Radio Éireann’s programmes and will be at their service once again with expert and practical advice about the arts and crafts of the handy man. In these days of high prices, more and more people are driven to tackle for themselves the various little jobs of ‘making and mending’ about the house which, in happier times, they would have handed over to a professional specialist. And, indeed, it is remarkable how much even the most awkward and incompetent of us can do in the way of minor repairs provided we have enthusiasm and a little practical knowledge. The necessary enthusiasm is not hard to come by, but the practical knowledge is another matter: more often than not books – the obvious source of information – seem to avoid the very points on which we most need guidance; in such a cast, Peadar O’Connor can almost always come to our rescue. There seem to be very few crafts with which he is not considerably more than superficially acquainted: and he has, above all, the gift of a vivid imagination which enables him to see the solution to a problem, no matter how difficult or unusual it may be almost as soon as it is presented. He is, too, very clever at explaining quite tricky operations verbally, so that his invariably practical suggestions are always easy to follow. In short, he is an invaluable guide, philosopher and friend to the handy man, and there is no doubt that his many ‘clients’ will welcome his return to Radio Éireann.

People used to write into the programme seeking his advice about DIY matters, such as objects they wanted to repair or clean or cure for example, to fix a bath or tap that sprang a leak, repair or clean furniture and polish it, repair windows or the roof of a house, how to dye rugs or wool or lay a concrete floor and much else. The numbers of letters he got were countless. John McGahern recalled his memory of that programme, explaining that the affection that adults had for the programme differed from that of young people:

My father was a devoted listener of a programme on the Athlone station, Making and Mending, with Peadar O’Connor. Peadar’s voice and presentation was so doleful and plodding that we used to make fun of it in secret: ‘You get the hammer, and you take the nail, and place the nail on the wood. Then you strike the nail with the hammer…..’

Others held an entirely different opinion about the programme as is conveyed by the following piece in Ar Aghaidh:

Each Tuesday for instance, at six o’clock, Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill talks about the year’s work. If memory serves me correctly, he spoke one Tuesday about how sugar and sweets are made. Another night, he described the harvest and its reapers. Domhnall, God bless him, superbly describes craftsmen and their work. Whether the craft be old or new, rural or in the factory, Domhnall is the one to inform you about all matters relating to it.

Others asked him how to make candles from goat tallow (geir) and he described how a seanchaí from Connemara told him that the candles Gráinne Ní Mháille brought with her to England when visiting Queen Elizabeth were made from goat tallow, which amazed all at the palace. He attempted to deal with the problems on a seasonal basis. Parents, particularly mothers, used to write to him before Christmas, asking how to make toys such as dolls and carts. That he had a wide listenership throughout the country is obvious from the handwritten scripts he left behind. These scripts contain accounts of who wrote to him, of the people from all parts of the country, many of whose queries and problems related to several persons. All the scripts were handwritten entirely by him before he went on air and had to be sent to Radio Éireann three or four days before being broadcast. His son Diarmuid used to deliver the scripts into the Post Office on Henry Street on his behalf. Domhnall wrote illustrated articles of the same sort for printing in Biatas for several years and a long article of his was published in 1958 in the Handbook of Muintir na Tíre. Maurice Gorham, who was Director of Radio Éireann, called him ‘the genius of making and mending.’

Domhnall made many filmstrips as teaching aids, designed by him in his own dark-room in 1940. He did this creative work entirely at his own cost, without support or recognition from the Department of Education. He wrote an article about this entitled ‘Súiloideas’ in Iris Choláiste na hOllscoile, Gaillimh, 1950-51. Here there are descriptions by Domhnall of the usual methods used for visual education in the classroom. He often lectured about these teaching aids in his capacity as a member of the Irish Film Institute and the Geographical Society of Ireland.

As has been mentioned at the outset, Domhnall was an outstanding multi-skilled man. He did his utmost to preserve the life and culture of the people of the country and to introduce these to the public at large. As a teacher, he had a special interest in the Irish language and its advancement. He understood the importance of education and learning to the child and adult. He devoted his attention to the large world of folklore and acquired professional knowledge of the native gamut. He secured a national platform for that richness about which he spread information in the realms of learning and communication. As a teacher, journalist and as a person of very wide skills, Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill has not as yet received the recognition he deserved.

Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill’s published work

- Máire Uí Chuinneáin

The state of Irish greatly improved with the establishment of the Irish Free State. The status of Irish was confirmed in the Irish Constitution and all that ensued from it. Apart from the importance of Irish in any other aspect of society, its advancement was sought especially through the educational system. In some ways, the Irish lobby was taken unawares of that stage, given that the numbers of teachers capable of teaching Irish were sparse and because there was a great scarcity of textbooks initially and for many years subsequently. Many means were devised in order to improve the situation, e.g. sending teachers to the Gaeltacht to learn Irish during the summer, the establishment of the preparatory colleges and of An Gúm to supply school textbooks, as well as basic books and translations into Irish.

The national newspapers of the country realised that the Irish language had become more important than hitherto. Financial matters are the main concern of newspapers however, and they do not waste printing space with reading matter that is not in demand from their readers. Two large English language newspaper companies provided daily newspapers in the 1920s, namely the Irish Times and the Irish Independent. At that time, the Irish Times had no interest in Irish language matters and this for ideological reasons that were well understood. The Independent was a strong supporter of the Saorstát and hence it was no wonder that this company was willing to publish Irish matter, however little, in their newspapers from the founding of the Saorstát onwards.

As a young teacher especially interested in the life and fortune of the Irish language, Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill emerged in timely fashion. As a devotee and teacher of Irish, he wished to advance it nationally in a way in which he personally could be most effective and that suited him at that time. He soon saw that only true enthusiasts bought any Irish language newspaper, but that a few English language newspapers were bought each week by every household. The latter were, therefore, better suited for exposing Irish reading material to the Irish public. Accordingly, he started providing the English language newspapers: Sunday Independent, Irish Independent, Irish Weekly Independent, Irish Press and Evening Herald from 1922 to the end of the 1940s. It is to that corpus that we shall now direct our attention.

Domhnall commenced his journalism on 5 February 1922 with an essay entitled ‘Education in Ireland’ in the Sunday Independent. From then on until 1925 an article by him appeared almost weekly in the same newspaper, over 100 pieces in all. In these pieces, he moved to and from topics, relating to study, literature, Irish language issues and life generally but he also extended his scope, most of the time beyond these fields. He furnished essays mainly on animals and birds, nature generally, literary matters as well as translations from French – the usual range of an author in any language. Thus he provided worthy reading material in Irish, at a respected journalistic and intellectual level that would satisfy a mature reading public as well as learners.

There was a strong connection between the Sunday Independent and the Irish Weekly Independent, first in that neither was a daily newspaper and secondly, that the same material was sometimes printed in both papers in both English and Irish, but this was not so in Domhnall’s case. He started writing for the Irish Weekly Independent in June 1925 and continued so consistently each week until almost 1942, providing up to 1,000 articles in all. This was a great writing achievement and it must be said that Domhnall was the person who most frequently of all, had pieces in Irish in any English language newspaper during that entire period. Given that the great variety of his writings for the Irish Weekly Independent has not been referred to elsewhere, the following classification of the topics therein is indicative of the state of the Irish language during that time and illustrates the range of Domhnall’s interests.

Translations

In 1925 a government scheme, An Gúm was established in order to publish school textbooks and other reading material through Irish. Creative work in Irish was being published but it would seem that not enough of this was being produced at a sufficiently high standard that contained a variety of subjects and styles adequate enough for the Irish language readership. A translation scheme was started from the late 1920s to the early 1940s in particular and an enormous number of books were translated into Irish under that scheme. Many writers undertook this work of translating, both full-time and part-time. The principal task of the scheme was to translate texts from other countries. Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill did his stint in regard to translating. He translated and had four books printed, one of which was in book format, namely, Robin Húid is a Cheithearnaigh Coille, and three others that were never published as books. Two of them were translations from French. Eachtraí Asail was published in the Irish Weekly Independent over 45 weeks from August 1931 to July 1932 and Éirinn na n-Éacht in the same paper over 34 weeks from October 1932 to June 1933. He translated another French work also: Sain Germain na Fraince, published in the Irish Weekly Independent for 15 weeks from July 1932 to October 1932. Yet another translation of his was Crann Coille, published there too, weekly in 16 issues from early January to the end of April 1934.

Scéal an Mhachaire Mhóir was the longest of his translations, consisting of one book, published in the Irish Weekly Independent over 103 weeks – almost two years – from early July 1929 to the start of 1931. This book was concerned mainly with cowboys, but sadly it was never published in book form, as it would have added considerably to the variety of reading matter for Irish language readers, particularly young people.

He translated stories by Hans C. Anderson, O. Henry and Oliver Goldsmith. A short essay of his was published in the Sunday Independent in January 1924 ‘Asal an tSean-Duine’ was its title and it was a translation of a chapter from a book by Sterne ‘A Sentimental Journey’. He retold ‘An Fear Sona’ by the Russian Anton Chekhov and ‘Staighre an Fhathaigh’ by Crofton Croker. He also provided his own version of stories from abroad and from France and about Saint Patrick. Thus his translation work consisted of a great variety of subjects and there is particular importance attached to having these stories available in print at that time. No stories of that kind were available in Irish and they were stories that would attract the interest of particular people. The stories created a platform for Irish in an English language medium nationally and helped to cultivate interest regularly in the Irish language. He had an essay printed in the Sunday Independent concerning the benefits of translation and, as is obvious from the catalogue of his work, he was translating various stories from then onwards. Domhnall was not the first or the last person to have material translated in an English language newspaper. This was a basic aspect essential to the code of the Language Revival that was always present. Neither was Domhnall the only person to have his translations published in one of the Independent newspapers.

Folklore Material

Domhnall had a special interest in folklore. He was a great collector of folklore. He was a member of the Committee of the Irish Folklore Society from 1936 to 1961. He collected the vast majority of the folktales that he had published. He, his wife and family used to go regularly to Carna on holidays and indeed he could not have come to a place richer in culture than Carna. It was there that he met the two famous seanchaís Pádraic Mac Con Iomaire and Pádraic Mac Dhonnchadha. Both of them hailed from the same townland Coillín in Carna. He collected all sorts of folklore from them, including myths, fairy stories, international stories, fiannaíocht and romantic tales. They narrated local folklore to him too: tales about fairies and magic concerning people, animals, bird, boats and certain incidents that had occurred many years previously. They informed him of the saints associated with the region such as Mac Dara and Ciarán and holy wells that were and still are there. Domhnall published long essays regarding Pádraic Mac Con Iomaire’s recollections of the year’s work in the Carna area and his own reminiscences. He published numerous short stories entitled ‘Aesóp I gConamara’ in the Evening Herald during 1941-42, which are contained in this book.

Domhnall also collected folk tales from outside Carna from the famous seanchaí Seán Ó Coileáin from Cor an Dola and another seanchaí from Inis Oírr Ruaidhrí Ó Tuathaláin. The ediphone was the recording instrument used by Domhnall. The Irish Folklore Society provided him with that in order to collect stories for the Society, on whose committee he served from 1936 to 1961. When all the stories had been recorded, he wrote them all out in his own long-hand. These stories were particularly rich. Particular importance also attached to them in so far as Domhnall provided a national platform for them in the country’s main English language newspapers at that time. Undoubtedly, these stories helped to foster interest in the Irish language and in native learning. A natural language was to be found in the stories that also contained fine phrases and words in Irish. Large ‘boulders’ of Irish were available in the mythical tales in particular – words that were not normally spoken in everyday use. He cultivated the practice of reading in Irish and through this material he encouraged people to become interested in their culture. Domhnall had a special interest in culture, folklore and in the life of people and he also understood the importance of collecting and preserving this richness, but he also realised the importance of having it printed, instead of leaving it on shelves where only the odd person here and there would catch sight of it. He was, above all the person who did most to provide the public of Ireland with folklore material in Irish in the most important medium of communicating at the time, namely, the English language national newspapers.

Crafts

Domhnall was very dextrous, having a strong interest in crafts. He got to know a superbly skilled craftsman Pádraig Ó hUaithnín from Dubh Ithir in Carna and amassed much information from him about carpentry. He published this information given to him by Pádraig as well as essays written by himself about carpentry in the Irish Weekly Independent in 1935, entitled ‘Seanchas Siúinéireachta’ and ‘Seanchas na gCeard’. He also had essays printed in the Irish Weekly Independent about the work of the shoemaker and tailor, their working methods and the tools used by them. Obviously, he had great respect for the craftsman which he indicated in another printed essay, entitled ‘Uaisleacht Lámh Oibre’.

Domhnall understood the significance of crafts in the life of the people, realising also that the day would come when these crafts would no longer survive. He was a great advocate of crafts in the life of the people and preserving their culture and that if that were not done soon they would go out of existence. He studied how this work was being done in other countries. Early in June 1936, he went to Copenhagen to examine the Cultural Museum there. He compiled a diary of his travel in the various places visited by him and of all he saw in the course of his study visit. One could say of this that it was a study of how the old way of life of the people and their working methods were preserved in the Cultural Museum there. He took many photographs of the places and various museums he had visited. He was greatly concerned that nothing was being done in Ireland to preserve the people’s life and culture. He published an article in the Irish Independent in 1938 about this issue. Many other eminent writers contributed articles about the same theme at that time.

Irish Learning

As a person working in the new native State and as a teacher, he understood the significance of bringing learning, history, literature, language and the Irish language movement to the public’s attention. During those years, therefore, he sought to fill informational gaps in those areas.

Educational Material

As a teacher and a scholar, he also realised how important it was to provide educational material to students and to anyone interested in education. In his essays ‘Tíortha i gCéin’, he minutely described the countries of the world, Continental Europe, Asia and Africa. He interestingly depicted the locations of these Continents, their rivers, lakes, mountains, plains etc and on their modes of living, as well as the people themselves. He also dealt with their climate and manufacturing, if such existed. He published other interesting essays about Egypt, its Pyramids and the ways of people’s lives thousands of years before Christ. All of these articles were published in the Irish Weekly Independent during the 1930s and 1940s.

Ordinary Journalism

He published further articles about various birds of the air and of the sea. He mentioned all their names in Irish, describing the habits of each. It is clear from this work of his, that he had studied them deeply. In one of these essays, he averred that the instinct of birds was stronger than human training. He used lots of proverbs in his essays. He described coastal food, such as carrageen, dulse and sloke and how it was harvested and how the carrageen and dulse were dried. This food was particularly important for health purposes. Many people used carrageen in the old days when they were ill.

His articles about various flowers contained their names in Irish and in English. He showed a special interest in nature, mentioning in his essays the importance to one’s body of taking time out and walking in the countryside.

Domhnall published essays in various magazines, among them one entitled ‘Súiloideas’ (Visual Education) in Iris na hOllscoile, Gaillimh, 1950-1951. That essay explains how a child or student learns lessons when they are displayed on the blackboard or through a magic lantern or diascope, as he called it. He stated that a great advance had been made, when the photographs were placed on a slide and electric light applied to it. Yet another instrument was named as the ediscope; and finally, both the ediscope and the diascope were brought together in the one machine. These were the usual instruments for visual education in the classroom.

He published various essays in English in the magazines Biatas and Muintir na Tíre. His articles in those publications were under his pen name Peadar O’Connor. He wrote about the care of carpentry tools, using illustrations in this essay published in the magazine of Muintir na Tíre. He also had an article published about making a concrete vat in Biatas.

A Pamphlet

He published an article about Saint Mobhí in 1930. This information concerning the life of the saint reflected his interest in the history of Church affairs. Saint Mobhí was the patron of Glasnevin, where Domhnall spent most of his life.

Photographs

Obviously, Domhnall took numerous photographs of the various places that he visited. His son, Cian O’Carroll, has presented 106 of Domhnall’s photographs to the Department of Folklore, UCD.

It is clear from what Domhnall achieved and traversed and wrote that he was never idle. He indicated his interest in the world at large and in the people he met during his life, describing precisely all that he saw and heard and where he went. He had the gifts of the writer to his marrow. This is not an analysis of his work – only a short account of his writings and work. Domhnall Ó Cearbhaill richly deserves credit as a writer, as a teacher, as a scholar and as one who did his utmost for his country and its language. It is past time to have his name and work kept before the public, particularly the Gaelic public. His work is far too valuable to be kept in boxes or on shelves. That is also what he would have liked himself, because he believed that things should not be forgotten. He himself arranged the publication of all that he had written during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. He and his generation have passed on to their reward, but the imprint of their pens still survives and out of respect for him, it must be maintained and placed once again before the public. The time has passed for doing this work, but perhaps better than never.